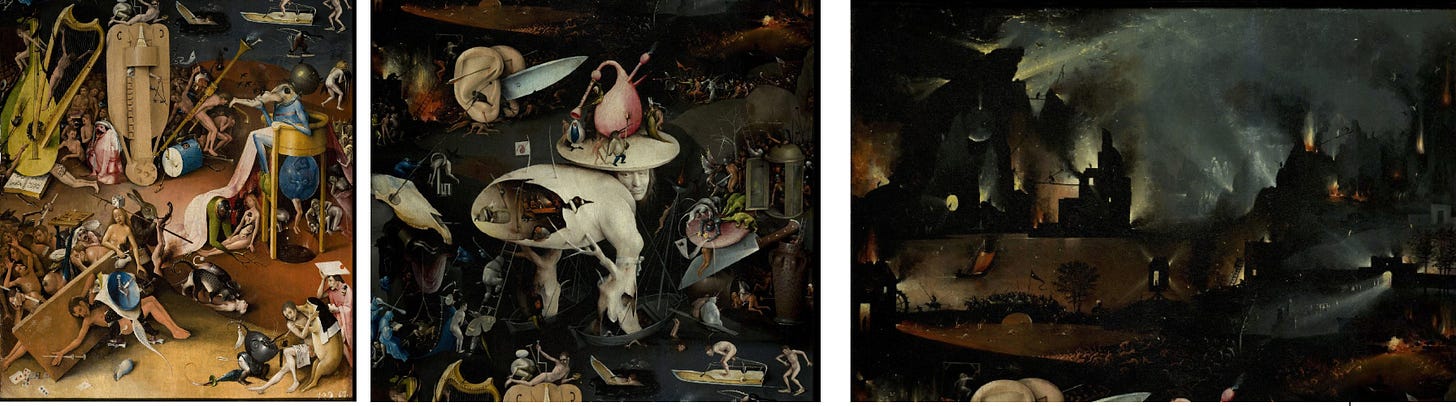

14. The 'Comic Opera' in the First Level of Hell

The remarkable lack of suffering among the damned might turn our view of the painting around

This comic interpretation of Bosch’s Hell is going to be a tough case to make, so let’s approach it with an open mind.

The proposition is: most of the suffering in the foreground of Hell – that is, the bottom third of the panel – is not really suffering at all. As the venerable historian Walter Gibson suggested, most of the victims are acting suffering. This comic opera sense includes visual jokes (the fundamental flute, ‘butt-music’, four-and-twenty-blackbirds and the cartoon figure vomiting into the cess pool). It is a different feeling from his Haywain Hell, or his Last Judgement.

Above this first section, in the middle third, we have more Bosch-type Hell, but the sense of universal horror only really gets going in the top third. Each zone, or level, seems to have its own culture of suffering. The sense of Hell intensifies in each level.

In the foreground, the suffering is sporadic and very often illusory. It is a theme park sense of Hell. The Hades Experience (exit by the gift shop). To evidence this counter-intuitive proposition, please let the jury consider exhibits A through I.

EXHIBIT A

Can we call this suffering? Proper suffering? Surely, this is more the attitude of a chorus line dancer in Broadway musical.

The open-mouthed man behind him is registering not pain, not anguish, not the metaphysical horror at being excluded from the presence of God. He, along with other gawkers, is looking at something remarkable offstage, something dubious, or shocking on the level of a Bill Burr set (‘Is he allowed to say that?’) – not something eternally and infernally punitive,

NB: The character on the left is looking at the Broadway star with interest. He seems unaware of where he is. None of them feel the presence of existential evil.

EXHIBIT B

This semi-decapitated man – in what way is he suffering? I agree a sword is half-way through his neck, but is he bothered by that? Is there anything in his demeanour that says he is uncomfortable? Does his mouth register pain? Does he have his little finger scratching his right eye, as people do when they are bored, oh God, so bored?

EXHIBIT C

These men are deep in conversation. One is listening with earnest sympathy. The other has a knife in his back. The knife hasn’t been slipped in sideways between two ribs, it must have cut through them, right next to the spine. There is nothing in his posture to suggest he is aware of this, nor is there in the attitude of his listener. They are fully occupied in what they have to share with each other. This is a deeper companionship and communion than anything in the centre panel. It is not a usual view of Hell. It isn’t Bosch’s usual view of hell.

EXHIBIT D

One of Bosch’s more disturbing demons – a cross between a countess and a screaming rat – is embracing a victim. He has covered his face in a way we might have thought was shame, horror, desperate contrition – but he is peeking. He is sneaking a glimpse at us to see if we are watching his performance.

As a further oddity, the demon’s fingers aren’t clawing or gouging. They look almost protective, almost caressing the back of his head. It mightn’t otherwise be noteworthy, but she is not the only demon with a delicate touch (see below).

EXHIBIT E

Our gambling friend has a sword in his chest. The blade has gone in vertically, breaking ribs or slicing through them. His out-of-shot hand has a short sword right through the palm. The rat demon has him by the throat so that while stabbing, he is also strangling him. It’s a belt and braces approach.

And what is our friend thinking, if anything?

He isn’t even indifferent. That is the face of a man quietly pleased with the way things are going. It’s more a smirk than a smile. Everything about his situation says suffering except his reaction to it. He is completely untouched by mutilation.

‘I hear Italy’s nice at this time of year. Not too much plague. I wonder if Caleken’s mother would let her come with?’

EXHIBIT F

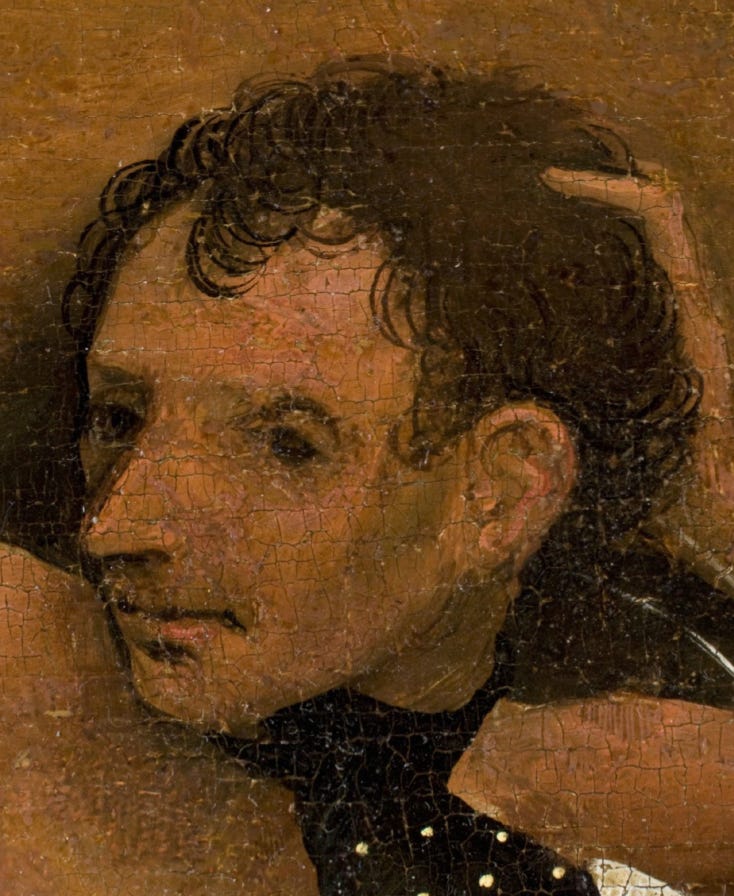

This young man, part of the choir, sits above one of Bosch’s most horrible demons – the fierce and furious fish demon. Those bloody, carnivorous eyes are alight with an infernal appetite. But the young man looks unconcerned. He looks almost . . . happy. He is part of the Boys in the Band.

EXHIBIT G

Whatever is going on in this chorister’s head is not the fear of eternal damnation in the fires of hell. He is projecting. He is emoting. He feels the spotlight on him and he’s responding to his director’s note: ‘Teeth and tits, dear!’

EXHIBIT H

The rabbit carrying home his human prey is a ‘world-upside-down’ trope taken from the drolleries of medieval manuscripts. The dead man being eaten by dogs has suffered, but this is undercut by the expression in the dog’s eyes (Bad dog! You know you shouldn’t be doing that!) Ditto for the demon dog ‘copping a feel’ of the unconscious woman above. They are guilty, but the guilt doesn’t stop them doing what they know they shouldn’t be doing.

Yes, the dead man with the fire bursting out of his stomach must be suffering. But Bosch doesn’t show us that. And he certainly was happy to show that particular agony of the damned in a previous Hell. He is happy to show us agonies in the next level of this Hell. Something different is going on here in the foreground.

EXHIBIT I

Our old friends (see post 2). The man really isn’t discomforted. A giant swine is nibbling his ear, the devil may be about to inflict the world’s greatest pain on his soul. He is concerned, if concerned at all, with his part in a comic narrative. Like his counterpart in Exhibit E he really couldn’t care less.

‘If Caleken’s mother insists on coming with, the whole deal’s off.’

TO CONCLUDE

In brief, and as with the other panels, there is no single explanation or description that fits everything. But these anomalies – if anomalous they are – do deserve more attention than they’ve received hitherto.

That’s not much of a conclusion, but there are two more Hell posts in the pipeline.