The Secret Delights of Bosch’s Garden

This highly-illustrated newsletter of Bosch criticism is uniquely suited to the Substack format – the text is closely integrated with the images, the chapters are short, and the case it makes will evolve over the next year or two.

Pls click on the Home page button to see the full archive.

The commentary – the result of a year’s in-depth examination of the painting alongside the Bosch industry’s main books and articles – is occasionally iconoclastic, always interesting and directly taken from the visual facts of the painting as revealed by this amazing zoomable technology.

Simon Carr says:

It began with an internet innovation, my year of looking at Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. It’s a fascinating, enigmatic work that becomes ever more fascinating and ever more enigmatic the closer you look.

In the real world, of course, you can’t get anywhere near it. The queues are too long, the crowd ten deep and the figures so small you need a telescope to see them. Bosch’s devils are in the detail. It’s a painting you really need to see close up.

That telescope now exists. Several websites offer a scalable, ultra-high-resolution image of the entire triptych . With a click of the mouse we can travel over the face of the painting and zoom into any part of it, down to the level of the craquelure. We mortals now have the access previously allowed only to high-status scholars, critics and art historians.

With one forefinger we can go from this:

To this

To this:

It’s available for anyone, its wonders to reveal. No queuing, no standing, no alcohol restrictions – we can look at it for as long as we like, and see something new every time.

Is there really anything new to see?

There are many, many remarkable things that aren’t in the Bosch canon of criticism. Look. These, the Staring People have never been remarked on. A dozen heads are upturned, some gazing, some straining to see whatever it is that is or isn’t there. You can’t ignore them once you notice they are there.

What are they looking at? What are they looking for?

It’s one of the secrets of the painting. When scholars become aware of it and incorporate it into their thinking (a process that may take five or ten years) they will doubtless tell us what they mean. For my money, they are the visual equivalent of David Bowie’s line. They are looking for ‘a crack in the sky and a hand reaching down to me.’ They are variously experiencing a premonition of the End Times.

Hell’s Holy Hog

Looking closely at the famous vignette has yielded a fascinating new interpretation. There’s an extended narrative in the cameo and it has an unexpected twist in the tale. The look of shock on the Notary’s face is the key to it. He has seen something about the Gambler that has appalled him. The solution to the puzzle will arrive in the Welcome email for those who subscribe (it’s free).

Lovely Little Things

And then there are things that are almost impossible to see. Perhaps that’s why they haven’t been seen. Ghosts, for instance. Four of them in the whole centre panel. There’s one in this scene, rather obviously once you know:

Here he is – palely loitering below and to the right of the man in the shell (that’s not glittering confetti being thrown over him, by the way – it’s the ghostly version of the bushes on the right).

Very well, they may not be ghosts, they may be lingering underpaintings of some sort. Then again, there may yet be more to it than meets the eye . . . Whatever the fact of it, you and I are now in the select minority of those who know these images even exist. Three more spectral apparitions exist in the centre panel. We’ll come to them in a later post.

Further fascination:

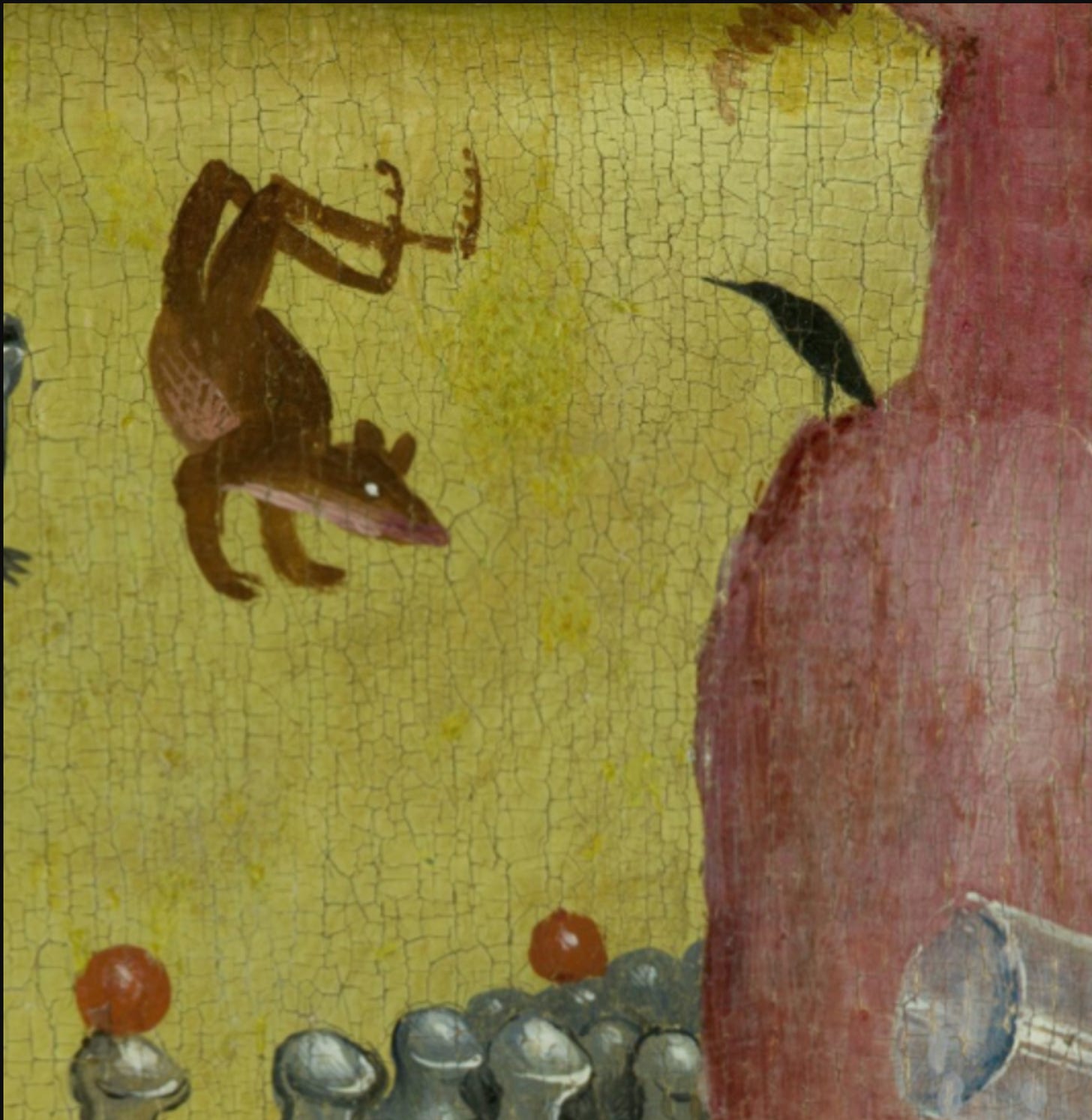

Zooming reveals different information at different levels of magnification. From a distance, this little fellow seems to be smiling.

But in close-up he looks like a hunter, a raptor: that’s the look on the face of a creature that’s going to kill something.

The triptych contains many, many vignettes and portraits, details and set pieces that have secrets to reveal to any of us who look closely enough, with fresh eyes.

This way of accessing a painting is purely modern. It wouldn’t be possible to get close enough to see this in the Prado; no book is going to reproduce all the details of the 92 square feet of the painting at this level. Critics and historians who haven’t had the chance to use this technique have missed many opportunities for close observation.

More Liquor Than Lust:

Here’s a curiosity that emerges when you look closely at it. There’s much less sex than everyone thinks. The centre panel is so innocent that it could be a country fête. Prince Edward wouldn’t look out of place. The real theme of the foreground isn’t lust but – in a new interpretation – liquor. Specifically, the 80 per cent proof, psycho-active aguardente Madronho.

But One Exceptional Lustful Vignette

On the other hand, the triptych has the most shocking sex art in the Northern Renaissance. These characters have emerged from the mud and sludge of the underworld. They are creatures of the Id. Her mouth has all the underworld allure of a sex organ. They are so much the essence of lust that they highlight the fact that there’s nothing comparable in the rest of the triptych.

Use this brilliant website to check what you see in the Substack posts. https://archief.ntr.nl/tuinderlusten/en.html. It is an ultra-high resolution, zoomable image of all three panels of The Garden of Earthly Delights. It is the brainchild of Pieter van Huijstee and Ingrid Walschots and deserves great praise and honour for this gift to the world of art appreciation.

Now all of us have the access previously reserved for high status scholars and historians.