1. Zooming in to Bosch's Garden of Delight

A new technology has revealed more about this painting than ten years in the Prado battling the crowds

It began with an internet innovation, my year of looking at Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. It’s a fascinating, enigmatic work that becomes more fascinating and more enigmatic the closer you look.

In the real world, of course, you can’t get anywhere near it. The queues are too long, the crowd ten deep and the figures so small you need a telescope to see them. Bosch’s devils are in the detail. It’s a painting you really need to see close up.

That telescope now exists. Several websites offer a scalable, ultra-high-resolution image of the entire triptych (try this wonderful one).

With one forefinger we can go from this:

To this:

To this:

We mortals now have the access previously allowed only to high-status scholars, critics and art historians – from the comfort and privacy of our sofas, we can browse the painting at the level of the craquelure.

No queuing, no standing, no alcohol restrictions – we can look at it for as long as we like, and see something new every time.

Is it worth it? What is there to see?

There are many, many remarkable things that aren’t in the Bosch canon of criticism.

Ghosts, for one thing. Four of them in the whole centre panel. There’s one in this scene, rather obviously once you know:

Here he is – palely loitering below and to the right of the man in the shell (who seems to be throwing some sort of glittering confetti over him).

Who the ghosts are or what they’re doing, nobody knows. But you and I are now in the select minority of those who know they even exist. Three more spectral apparitions exist in the centre panel. We’ll come to them in a later post.

Further fascination: zooming reveals different information at different levels of magnification. From a distance, this little fellow seems to be smiling.

But in close-up, there’s a peculiar intensity of purpose in his face. He looks like a hunter, a raptor: that’s the look on the face of a creature that’s going to kill something.

This way of accessing a painting is purely modern. It wouldn’t be possible to get close enough to see this in the Prado; no book is going to reproduce all the details of the 92 square feet of the painting at this level. Critics and historians who haven’t had the chance to use this technique have missed many opportunities for close observation.

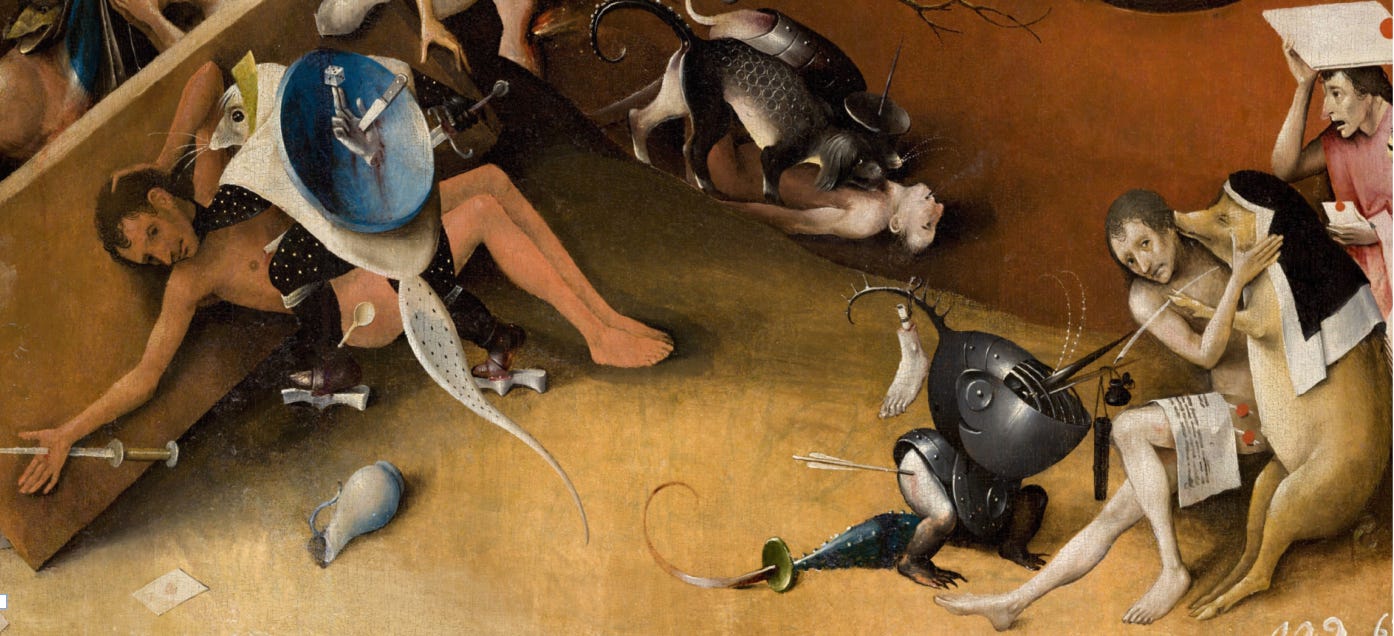

This famous scene in Hell, for example has a secret. The Holy Hog is nuzzling at a man’s ear to get him to sign some sort of legal document. But there’s another chapter in the story and it ends with a terrific twist – again, one that isn’t in any of the text books.

Subscribe for free to see what the story here really is (clue: the shock on the face of the legal assistant is the start of it).

Am looking for your X posts on this, but can't see them?

They are pointing, you're right. Have a look at the substack entries 12 and 13 where I go into it/them (and the Staring Birds) in more detail. In my interpretation, they are pointing to a mystery that in its turn points to the central mystery.