Am just going back over the videos, to add the script for your convenience. It is transcribed via an AI program – this one has decided to include the a cappella interlude, so I’ve left that in, as it rather adds to the sense.

TEXT OF VIDEO

The most famous triptych in the world has a secret hidden in it. It is a secret that has been kept for 500 years. It is so well hidden because the secret has been concealed behind another secret.

And that secret is so well buried that Bosch has hidden it even from himself.

But because he is a great artist, he cannot hide it from us.

The first clues that this secret even exists we find here, hiding in the five folds in the middle ground of the centre panel, where we can't help noticing, without being in the least filthy-minded about it, the prodigious number and the brazen ubiquity of phallic symbols.

They are everywhere, a forest of Freudian images. Mind you, there are symbols and then there are representations. You might be tempted to say, Speak for yourself, mate, but I suggest there's nothing symbolic about this one.

I even wonder whether it might be some sort of, how to say it, self-portrait. Because with the intensity that suggests a personal connection, Bosch has placed this phallus in front of probably the single most obscene image in the entirety of Renaissance art.

This bulbous penile sheath, with its horrible terrible thorns, its cruel blood-tipped briars, speaks of revulsion and horror and self-loathing.

The diabolical nastiness of this sex thing, emerging from a grinning ball of spikes, it makes the rest of the imagery look almost comic. BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM BUM B–

What we are looking at is the artist's deepest urges, his subconscious desires and instincts. They are surging up out of his interior with all the force of a life that will not be suppressed.

And looked at like this, it's clear there's something unruly and upsetting but ultimately unignorable going on in Bosh's soul. And that is the start of the secret that is hiding the real secret.

The question is does any of this penile symbolism translate into action on the ground? Are the men rampant as critics say they are? Are they lusting after the females? Are they after ravishing the women? And the answer to all these questions is no.

The counterintuitive fact is the men are far more interested in each other than they are in the women.

In the bath of Venus the bathing beauties are bewildered because not one single man is looking at them. They are gloriously, invitingly, seductively naked and no one outside the pool pays them the blindest bit of attention.

The men are either preoccupied with each other or, I'm sorry to say, with themselves. This man is suspiciously engaged in what seems to be a solitary pursuit.

This one seems to be agitating himself quite openly, shocking the man next to him.Here a twosome are closely involved while one decent citizen gestures as if to say get a room. Another behind him wears an expression of astonished or possibly horrified interest. In the same way the man here on the right is bent over his, shall we say, private concerns while a background face has a mouth formed into a fascinated ooh.

Moving along now, let us proceed to Bosch's most visible obsession. How the artist is fascinated with and fixated on the rear end of humanity. Most of the backward paths belong to males but a few are female.

This lady in the foreground is a classic callypigene (that is ancient Greek for beautiful bottom) as are these bathers in the bath of Venus but the vast majority of the buttock work is male. Quite a few of these rumps are intended to be comic. It may be Bosch's way of dwelling on the fascinating body part without revealing the intensity of his fascination because he's only joking when he shows this musical notation (written perhaps on a bass clef).

Only joking with this musical embouchure, only joking with the ultimate in Netherland humour, the famous four and twenty blackbirds flying from their pipe. So far, so innocent, although those of a suspicious nature may sense that the choir master's tongue isn't exactly the perfect epitome of innocence.

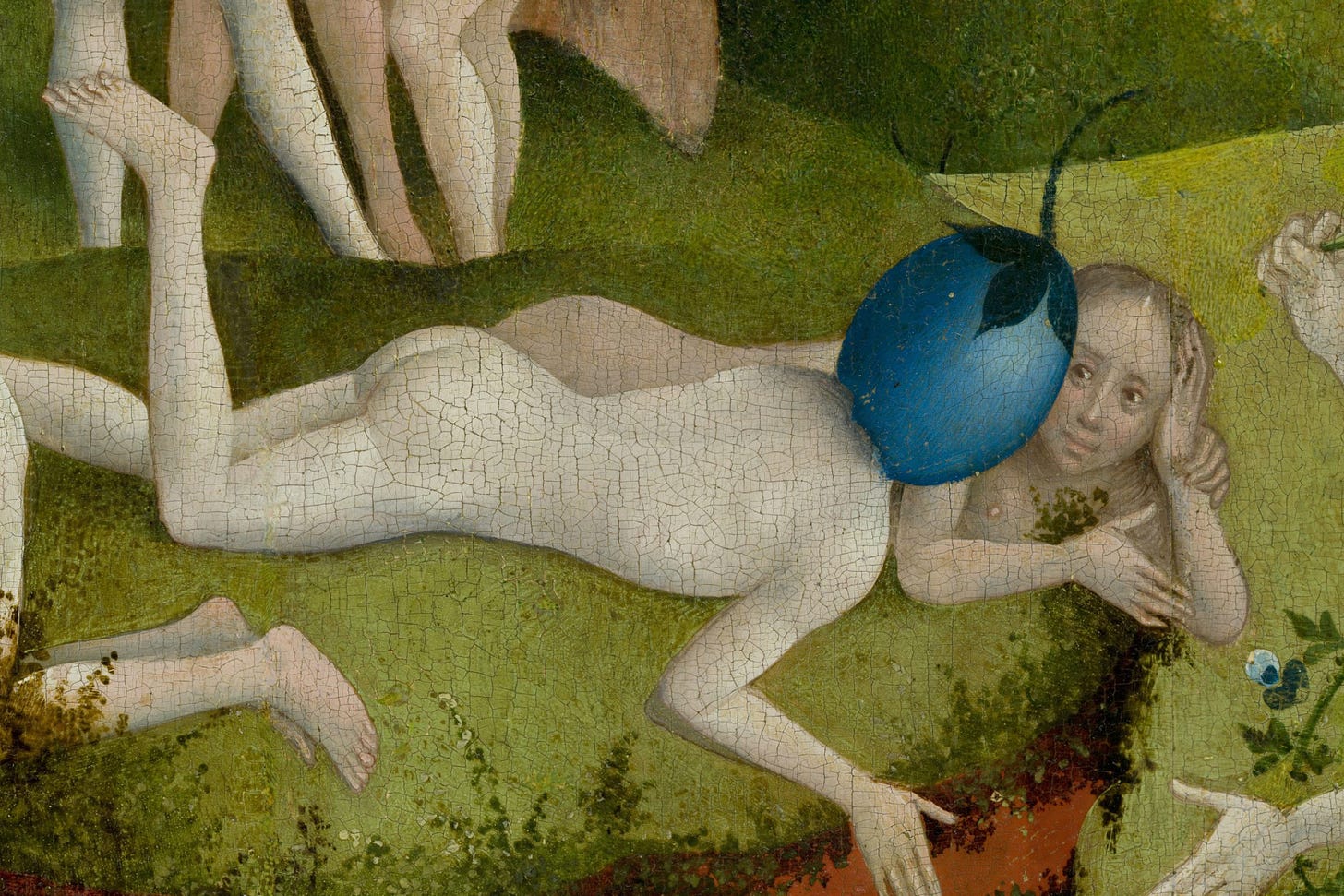

And is there just a little too much artistic commitment to this perfectly pert posterior, such that Bosch has had to quash the erotic potential by giving him a piece of fruit for a head?

This is harder to dismiss as a joke.

The acrobatic flirt contorts himself to show off his attractive asset. It has astounded the boy behind. It is a thunderclap. His fists are balled. His mouth is open, his eyes wide. He wants to throw himself forward, to pounce.

Bosch lightens the scene a little, but only a little, by the eye roll of the youth behind. He's seen it all before and clearly the delightful derriere works every time.

This one has no comedic escape route. It is a languorous pose, a sinner suspended in the first level of hell. But it is graceful, a balletic idealisation of the loveliness of suffering from the elegant fingertips down the long, lithe body line to the centre of Bosch's obsession. Stripped of its aesthetic, it is a pretty dangerous blasphemy.

In modern language, it is a semi-pornographic seder masochistic parody of Christ's crucifixion. As a piece of graphic sacrilege, no less than a piece of buttock worship, it has been given very considerable artistic attention and creative energy. But for pornographic masochism, there is an even more graphic example.

Let us follow Bosch a little further into his shadows, into what we might call his midnight desires. The fiend is greedy. He is hungry for that tender, bending flesh.

But he is only drawn to what has been volunteered. The kneeling posture is an offer, a request to be caressed and possessed and devoured by a demon. Given what we have already seen of Bosch's interior, it's possible to think he is implicated in this offer himself.

Let's leave that where it is and return to daylight. We've seen the phallic, we've noted the physical, but the most powerful and engaging evidence lies in the emotional There are, astoundingly, six scenes of men hopelessly and romantically yearning for another man. The scenes have been hiding in plain sight for 500 years.

No one seems to have registered them. To be fair, they are far from obvious. But once you see them, you will never un-see them.

It was this hand that first gave me the clue. It is tickling forward in an incy-wincy spider way. It belongs to the man in the background.

In front of him, a handsome young man is trying to entice a woman with one of the addictive, psychoactive madrano berries. It isn't working. She is dead eyed, ignoring him.

Right behind them, in touching distance, the young man with half-hooded eyes and a kissy kissy gap between his lips is gazing longingly on him, his tickling fingers out of sight, blamelessly itching towards the object of his desire. He will never arrive where he wants to be. The same sort of situation is happening here, though the dynamic differs.

An aristocratic sexpot has a vine coiling round her upper thigh and a secret weapon behind her back. She is confident of having her way with the high-minded nobleman. He is unaware of her designs on him, but more particularly for our purposes, he is equally unaware of the man behind, who has a dreamy expression, a swelling bottom lip and a secret smile as he gazes with undeclared longing on the man in front of him.

And over in the other corner, yet again, the same scene takes place. The man with the pointing finger is trying to engage the attention of another strangely dead-eyed woman. He is all unaware of the devouring look of yearning behind him.

That hopeless lover also has the pout and the little whistling gap between his lips. In the cavalcade, there are more examples.

Here, a keen, very young and impressionable youth has developed a life-changing crush on the noble, leaderly figure. He will never have the words to express it.

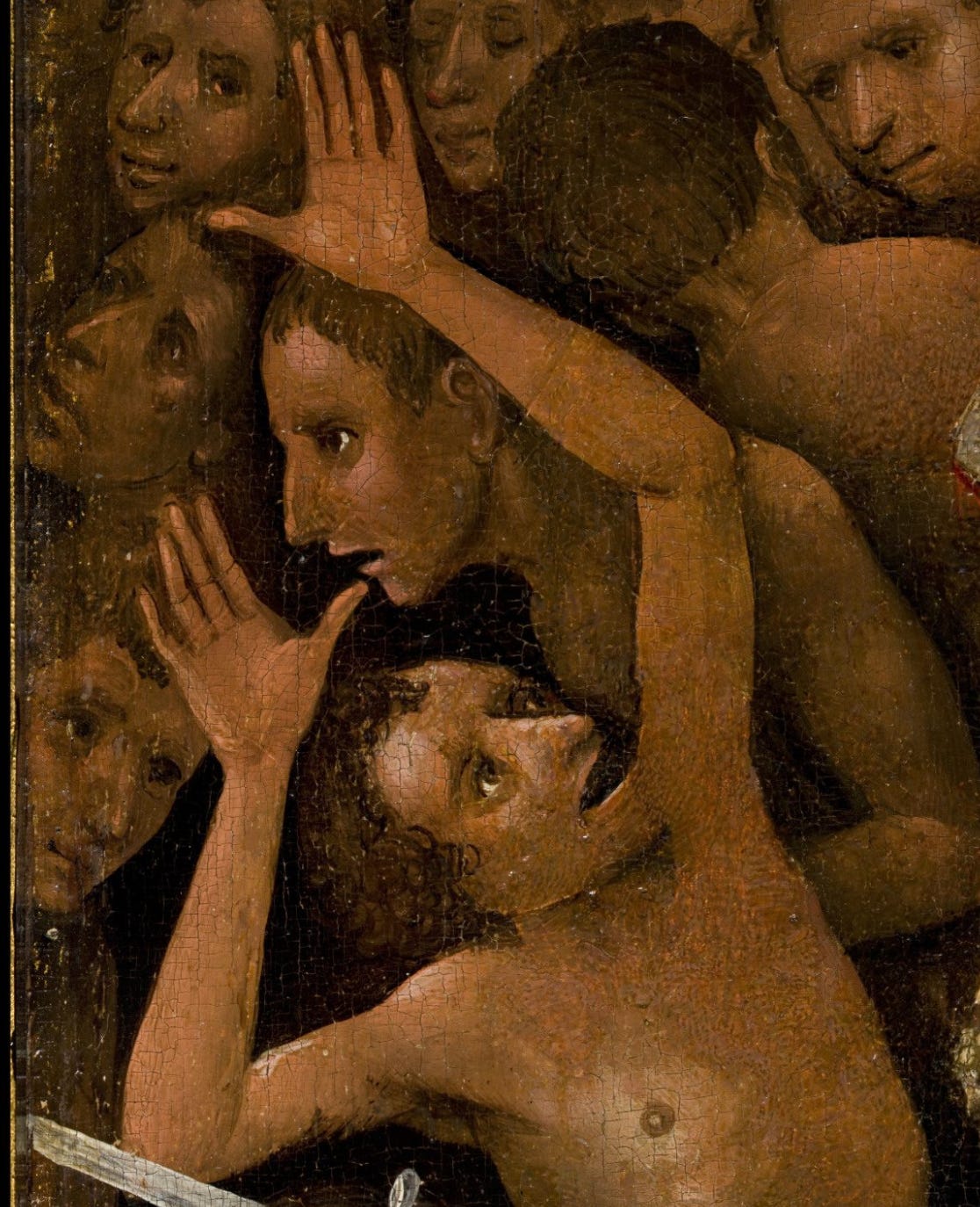

And here is the other end of this sort of affair. The man on the right wants out of it all. His gesture is dismissive. He's had enough. The man in the middle tries to stay him with a hand on his arm.

The victim of lost love is destroyed. His world has collapsed. He is wailing like an orphan child in the wreckage of his life.

It is amazing that Bosch portrays this so graphically and so compassionately. And so we come to the synthesis of all these elements in one of the most extraordinary images of the Renaissance. It is the most sympathetic, the most complicit portrait of a gay man.

Homosexuality was the sin so heinous that it was said even the devil did not dare name it. A sin so feared that 80 men were burned alive for it in Bosch's region in his lifetime. Yet here he is hiding in plain sight.

This sexual icon beckons us with one hand, welcoming us to his world. He has artfully tousled, bed-ready hair. He has sleepy, come-to-bed eyes, a reluctant, knowing smile at the edge of his lips.

His seductiveness is rendered in the full knowledge of the dangers, spiritual and emotional dangers, threatened by the blood-tipped spike of a bramble hurling viciously towards his rear. Indeed, the quarrelsome shell in which the three of them are pictured, it is characterised by these spikes surrounded by them. The threat is explicitly made but judgement is not passed.

And this is the unexpected twist in the tale. Bosch, the moralist, the castigator of sin. He does not condemn these romantic and sexual engagements.

Even in the garden's hell panel, the flamboyant choir boys are treated indulgently. They are not tortured, they do not suffer. Their exaggerated Boys in the Band theatrics speak to us across the centuries.

That this unruly homoeroticism has forced its way out from Bosch's Id might help explain the tree man who dominates hell. The intelligent renaissance face shackled to the body of a freak, a monster, a man horrified what he has secretly become.

So here we are.

Has the case been made for a strong gay element in the garden of earthly delights? To recap, we have seen

The phallic symbolism embedded in the architecture

An obsession with the bottom end of humanity.

We've seen the absence of male interest in the women and the intense emotional connection between men.

And finally, the most astonishing fact, the most revealing fact, that Bosch, he does not condemn these men.

That is the secret that conceals and causes the deepest secret of all. It involves the complete moral, theological and cosmological collapse of the artist. It would be funny if it weren't so terrible, but it is a bit funny as well.

Even Bosch thinks so.

Share this post